Vaccine History

Innoculation is the act of immunizing a person by introducing a substance that will protect against a disease. With regard to the history of smallpox innoculation, there have been two distinct methods:

The first (and less effective) is called variolation.

The second (and far more effective) is called vaccination.

Variolation Development and Effectivness

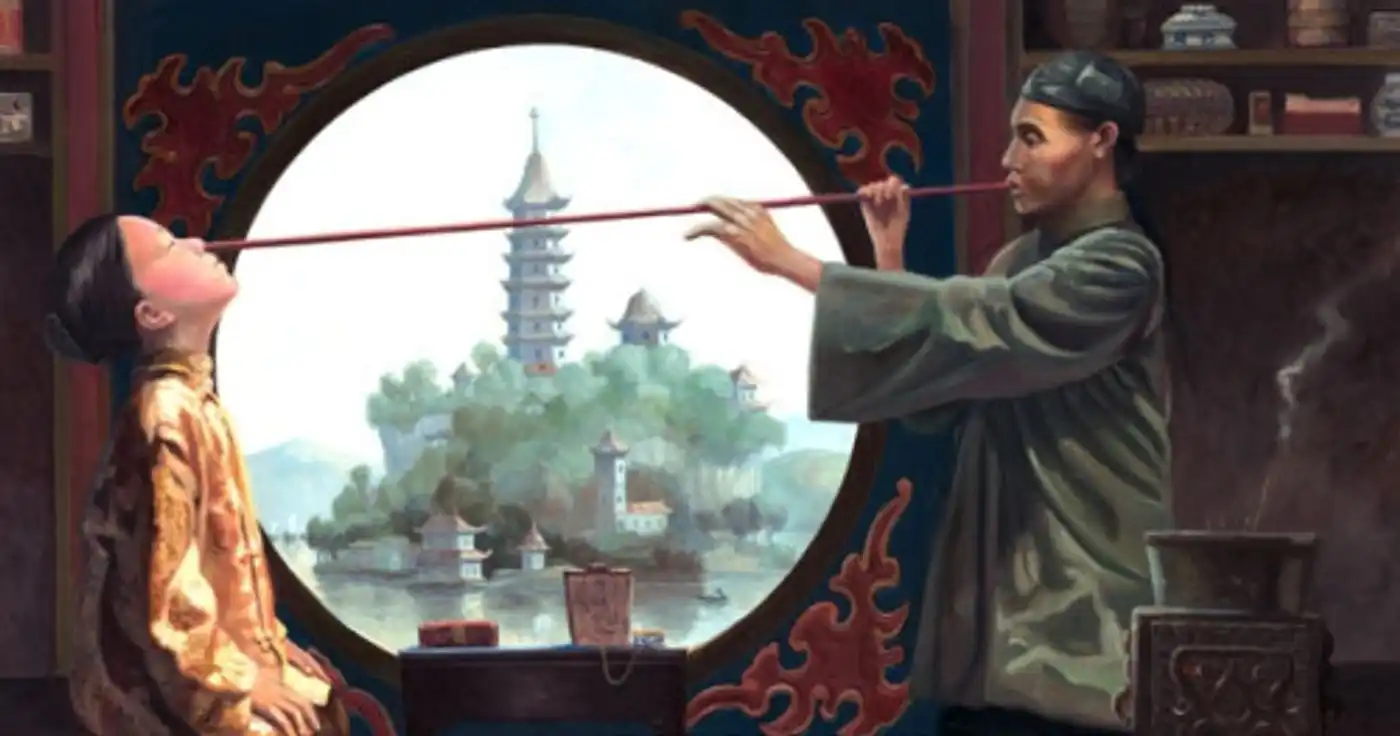

Variolation was developed and practices in Asia for centuries before the technique spread to Africa and the Middle East. It was only in the early 1700s was variolating was adopted in Europe and North America. Variolation consists of taking substance from the pustules of patients suffering from a mild form of smallpox (variola minor) and then intentionally inserting that substance directly into a patient’s body through a small cut, or by blowing crushed bits of the dried scabs into a patient’s nose.

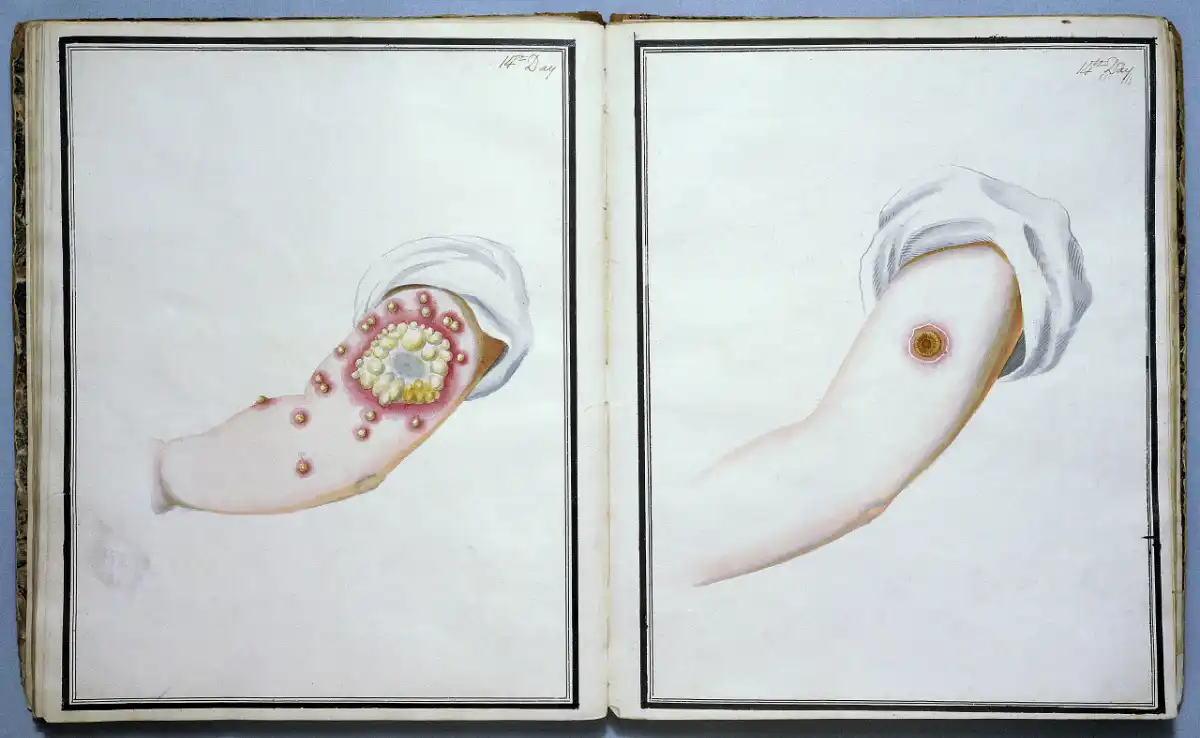

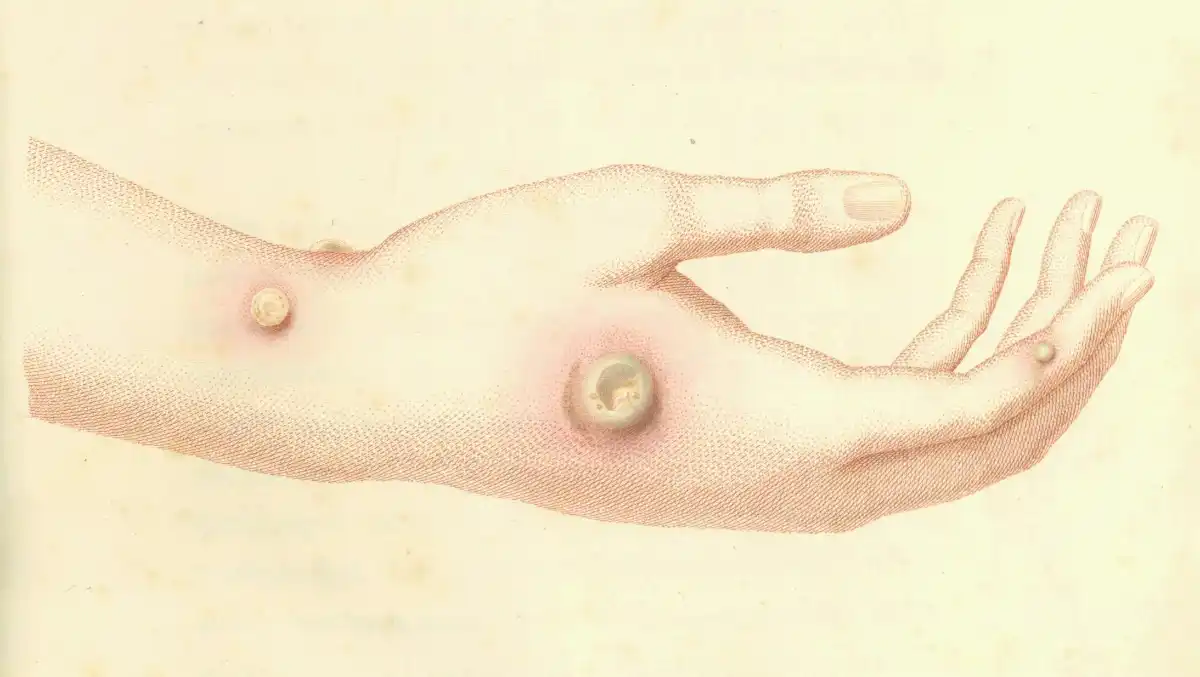

Up until Edward Jenner invented the first vaccine in 1796 the only effective prophylactic to prevent a person from catching smallpox after infection was variolation. Variolation necessarily resulted in a patient contracting a mild form of smallpox. Roughly 2% of variolation patients died as a result of inoculation (as compared with 30% who contracted smallpox naturally). Importantly, variolation patients were infectious to others during the time that they developed pustules, and as such, for variolation to be successful in preventing, as opposed to sparking, an epidemic, patients needed to be quarantined until they recovered from the outbreak.

1796: Invention of the Smallpox Vaccine

Using the same inoculation principle as variolation, vaccination consists of injecting the less dangerous cowpox virus into a person to produce an immune response that protects patients from smallpox. The word “vaccine” comes from this original discovery: vacca is latin for cow. Vaccination was invented by Edward Jenner in the 1790s when he observed that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox seemed to be immune to smallpox. Jenner then intentionally inoculated a boy with substance from a cowpox sore on a milkmaid’s hand. This resulted in the boy being immune to subsequent exposure to the smallpox virus.

Vaccination was initially dependent upon fresh supplies of cowpox pus. And the cowpox disease was only endemic in certain parts of Western Europe. By the early 1820s physicians were widely practicing the technique of retrovaccination which consisted of taking cowpox pus from a human and then re-introducing the disease back into a previously healthy cow so that the cow could then get sick with cowpox and produce new sources of human vaccine. Soon, effective human vaccines were also being made from horsepox pus.

By the 1850s vaccines were saving thousands of lived annually. In 1853 Britain made the vaccination of infants mandatory (strict penalties could be imposed on parents who did not get their children vaccinated). And in 1862 the British parliament made variolation illegal (due to the fact that 2% of patients died as a result of treatment, and because if not accompanied by strict quarantine it could result in new smallpox outbreaks). Variolation, however, continued to be widely practiced in certain parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Ethiopia, among other impoverished countries, up until the 1970s.

The Spread of Anti-Vaccine Ideas

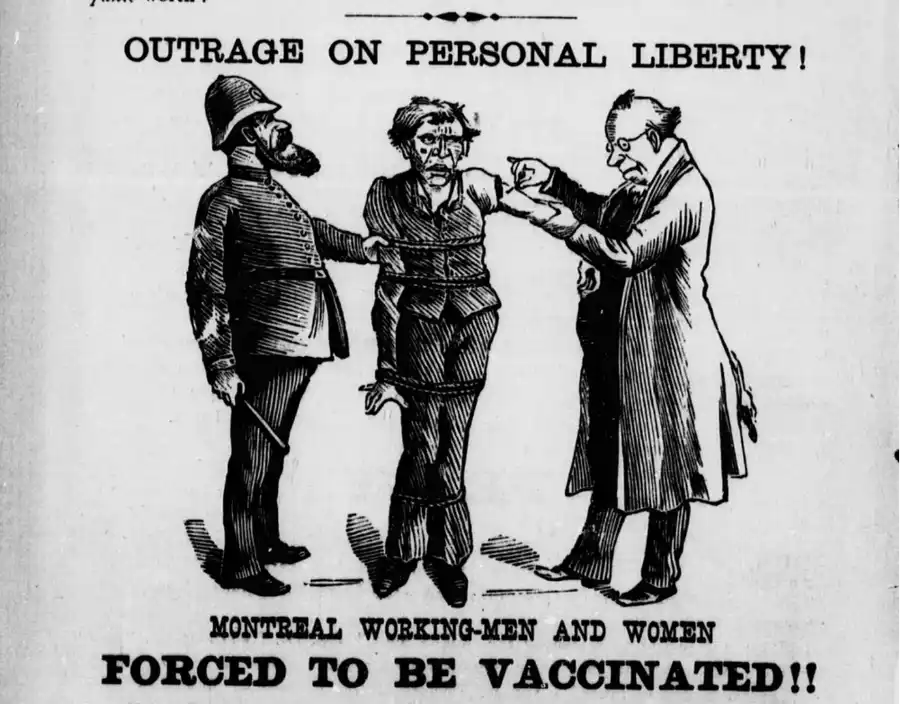

Opposition to vaccine is as old as vaccine itself. In the nineteenth century pro- and anti-vaccinationists each used science, religion, and the rhetoric of human rights, to justify their positions. Some nineteenth labour organizers argued that compulsory vaccination was an effort to control and remove working class people’s rights to bodily autonomy.

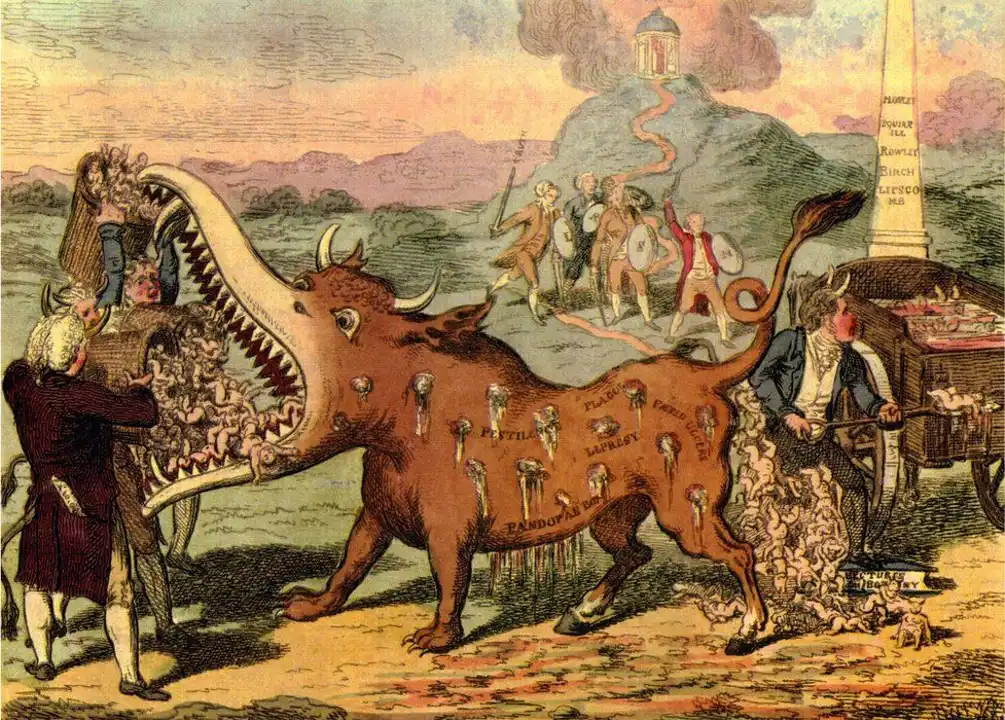

More extreme anti-vaxers asserted that vaccine derived from cows was designed by the business elite to turn working class men into the equivalent of exploitable docile cattle. Certain Christians opposed the vaccine because they felt it contravened God’s will by putting substance from animals into humans undermining the Biblical teaching that humans alone were created in God’s image. Among some Catholics, a dogmatic fatalism discouraged people from availing themselves of the vaccine.

It was common for people in the mid-to-late nineteenth century to argue that susceptibility to smallpox was due to a combination of both infection and a person’s moral/physical constitution. Many reformers advocated that alcoholics and prostitutes should be compelled to receive vaccine due to their weaker constitutions, while healthy and morally upright persons could decide for themselves in vaccination was worthwhile. Some Indigenous people feared vaccines because they did not trust the settlers who administered it: others, applying Indigenous world views, considered smallpox a spiritual disease and did want strangers inserting serum from a diseased cow into their body.